Since the first exhibitions with Alfred Stieglitz’s circle in the 1920’s, Georgia O’Keeffe’s art has always been regarded as distinctively female. The connotations of the essentialist female discourse attributed to O’Keeffe have evolved throughout the 20th century. It has shifted from the male-centred discourse promoted by Stieglitz, which posited O’Keeffe as a sexual yet passive agent, to a discourse of subjective sexuality. Feminist theorists in the 1970’s referred to O’Keeffe as a pioneering woman who claimed her sexual citizenship, by subverting the masculine-feminine/subject-object role traditionally attributed to woman, and thus introducing an idea of “sexed subjectivity”.1 Why, then, did she consistently deny the obviously genital connotations in her art throughout her career? How can we, as contemporary and image saturated readers, negotiate between the obvious sexual connotations in her work and O’Keeffe’s own claims about womanhood and femininity? What are we to make of her flower paintings? Did she contribute at all to the marginal myth of Woman? Is it time to reclaim the sheer ‘cunt-ness’ of her flowers?

Link to publication: Orlando Magazine

Photos

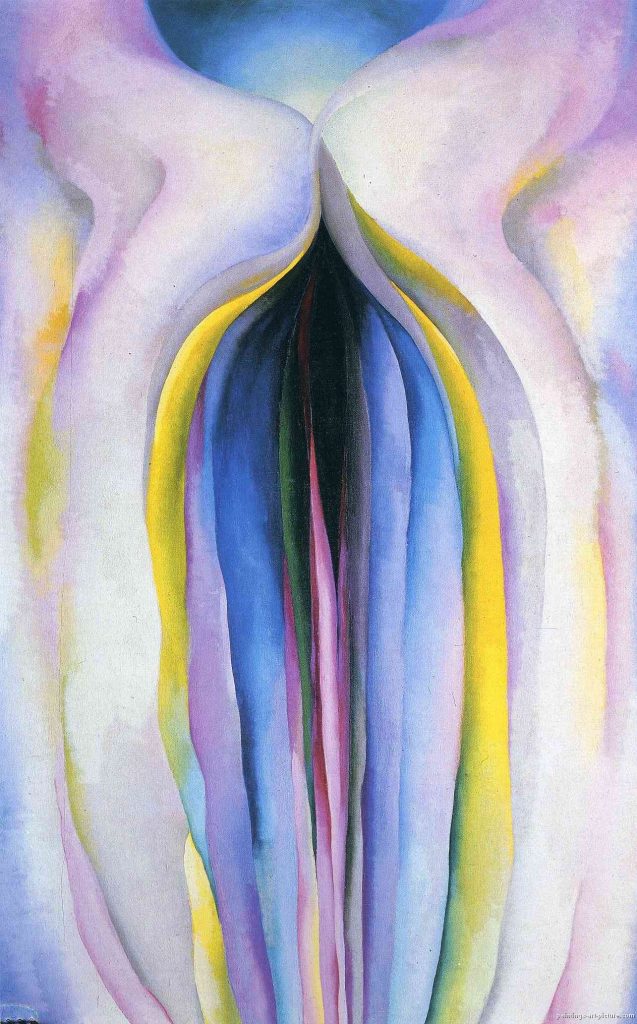

- Georgia O’Keeffe, Grey Line with Black, Blue and Yellow, c.1923

- Georgia O’Keeffe, Blue Flower (1918). Pastel on paper mounted on cardboard, 50.8 × 40.6 cm, Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, New Mexico

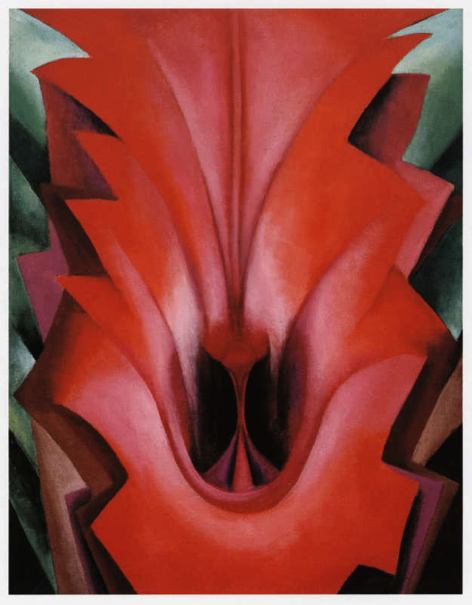

- Georgia O’Keeffe, Inside Red Canna (1919). Oil on canvas, 55.9 x 43.2 cm, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago.